|

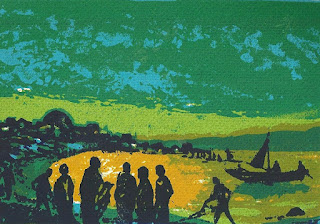

| Christ Takes up His Cross, Anna Kocher, 2006 |

But he also said “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me” (Luke 9:23). The way to relationship with God, to the full life Jesus promised, is through Jesus himself, but also through following the path he shows us, walking with him the road of sacrifice and self-denial.

Following the Way of Christ starts with a willingness to set our native loyalties aside. Jesus said again and again: leave your nets, your fields, your money, your life, and come, follow me. The early believers understood that the first step of the Christian journey was a step away from all prior allegiance, including allegiance to self, to comfort, safety, the right to be right, the mistaken idea that somehow we, on our own, are good people, better than those others.

The Apostle Paul understood this completely:

If someone else thinks they have reasons to put confidence in the flesh, I have more: circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; in regard to the law, a Pharisee; as for zeal, persecuting the church; as for righteousness based on the law, faultless. But whatever were gains to me I now consider loss for the sake of Christ. What is more, I consider everything a loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whose sake I have lost all things. Philippians 3Too many contemporary Christians assume that today the first step is somehow different, somehow less demanding, that we can keep our old loyalties and still fit Christ in. But to follow Jesus, even now, requires a willingness to step away from tradition, denominational assumptions, national pride, comfort, safety, confidence in our own intellect or education, the mistaken idea that somehow we, on our own, are good people, better than those others.

I start here: I am a fallen, broken person, jealously loyal to my own ideas, selfishly committed to my own ways of seeing, in need of a hand of grace to help me stand free of the misguided assumptions that hold me hostage, that whisper I’m somehow of more value than those others not like me.

I need help to start on the Way, and I need help to continue. If Jesus is the Way, then we’re called to live like him, visible agents of healing, compassion, reconciliation, forgiveness. Before creeds, before denominations, before tee-shirt slogans or bumper stickers, the early Christians were known by the visible difference in their daily lives. They embraced lepers, prostitutes, Roman soldiers. They fed widows and orphans. They refused to retaliate when faced with persecution. They offered healing to enemies, welcome to wanderers unlike themselves.

Those early Christians were so convinced of the lasting love of Christ they turned and offered that love to those who maligned them, scorned them, punished them. Unevenly, imperfectly, they walked day by day in the Way they had been shown.

|

| Jesus Calling Disciples, John Mosiman, USA, ca. 1970 |

Christ is not only preached through His own disciples, but also wrought so persuasively on men’s understanding that, laying aside their savage habits and forsaking the worship of their ancestral gods, they learnt to know Him and through Him to worship the Father. While they were yet idolaters, the Greeks and Barbarians were always at war with each other, and were even cruel to their own kith and kin. Nobody could travel by land or sea at all unless he was armed with swords, because of their irreconcilable quarrels with each other. Indeed, the whole course of their life was carried on with weapons. But since they came over to the school of Christ, as men moved with real compunction they have laid aside their murderous cruelty and are war-minded no more. On the contrary, all is peace among them and nothing remains save desire for friendship. (On the Incarnation)I admit, as followers of the Way in the 21st century, we face a challenge not known to those new Christians of an earlier world. We carry the heritage not only of those whose lives mirrored the example of Christ, but also of those who in the name of Christ went on with their war-minded ways, killing and conquering, justifying slavery and sexism, suppressing scientific study, shouting down opponents, carrying signs saying “God hates.”

No one said the Way of Christ would be easy. The call of love is always costly.

So we start with that other first step of the Way: confession. Not only confession of our own sin, failure, falling short, but confession of the falling short of those who have gone before, those who even now misrepresent God’s goodness and make the word “Christian” a sign of judgment rather than of hope.

Vinoth Ramachandra, Sri Lankan theologian who has surely seen more than his share of colonial misconduct in the name of Christ, notes “it is with a flawed and faithless people that the Christ has stooped to pitch his tent and link his name. Any sharing of the gospel within a pluralistic world, after two millennia of ‘Christianity,’ has to begin with humble acknowledgement of betrayals of the gospel by the church itself.” (Faiths in Conflict? 1999 p. 168)

Turning from our tribal loyalties, confessing our misrepresentation of the gospel and complicity in a culture skewed to its own good rather than the good of all, we start on a Way that leads us ever deeper into humility, deeper into the longing for wisdom, the repentant awareness of our own lack of love, our own inadequacy in the face of complex, overwhelming need.

|

| From the Gospel of Matthew Otto Dix, 1960, Berlin |

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom

for the prisoners

and recovery of sight

for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

to proclaim the year

of the Lord’s favor.” (Luke 4)

This is part of the August synchroblog, "Follow." Links to other posts will appear soon.

This is also part of an continuing series about faith and politics: What's Your Platform?

More than ever, I welcome your thoughts about which issues to consider, as well as your insight, comments, and questions. Look for the "__ comments" link below to leave your comments.