|

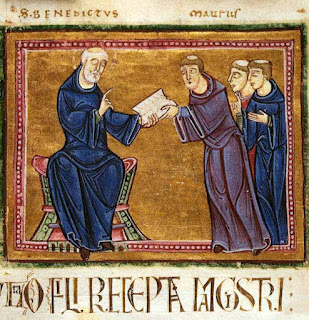

| St. Benedict, Herman Nieg, Austria, 1926 |

Apparently, 8th century scribes, puzzled at Benedict’s use of the word “conversatio” – implying an ongoing process, happening across time - assumed he meant “conversio” - a one-time change, a completed event. The error wasn’t discovered until 1912, when Cuthbert Butler, Benedictine monk, abbot, and church historian, consulted the earliest manuscripts for a new edition of the Benedectine rule, and replaced “conversio” with Benedict’s “conversatio.” In the century since he reclaimed the original term, much has been written about what Benedict meant by his use of the word “conversatio.”

I’ve been thinking about what matters. Somehow Benedict’s phrase “conversatio morum” cuts close to the heart of what I find most important.

For me, conversation matters deeply. I learn best by seeing the world through others’ eyes. I love wandering outside with friends who know bird songs, butterfly habits, where to look for hidden owls. I want to see what they see, know what they know.

And I love sitting in other people’s homes, sitting on the front stoop in neighborhoods not my own, hearing a different cadence of life, trying to understand family, community, value, from a different angle, a new perspective.

I sat last week in our church’s food closet line, waiting my turn to collect food for a friend. I listened to the conversations around me: lost jobs, a home fire that upended a fragile family, a man who lives in his car, preparing for colder weather. I talked with a woman who knows little English, spoke with another no longer able to walk without a cane. Watched as casual acquaintances from church walked by, noted me, and wondered: Why is she in line here? Breathed, just a little, the embarrassment of needing help. Of being on the receiving end.

I’ve been puzzling over the interplay between conversation and conversion, the ongoing conversion Christ invites us to: the continual call to follow, the ongoing change from selfishness to love. We’re called to be like Jesus, willing, like him, to identify fully with those on the wrong side of the equation. Willing to sit with the hungry, the broken, the contagiously diseased, the one of lowest reputation.

Conversation is impossible without humility. Humility is prequel to conversion.

I grew up in a faith tradition that saw conversion as a one time decision. Confess your sins, pray the sinner’s prayer, trust Jesus as your savior, cross the line from the unsaved to saved. Step from wrong to right.

Some of those I watched in that tradition walked on from there as impervious as they began, as proud, as hard of heart. They gathered their sense of rightness around them like the Pharisees’ robes, pronouncing judgment, dispensing unsought opinions with no trace of wisdom, humility, or kindness.

Others displayed that “conversatio morum” Benedict described. Bible open on the kitchen table, lives open to the pain and wisdom of others, hearts receptive to the Holy Spirit’s whisper, they demonstrated an ongoing change, continuing growth in generosity, forgiveness, love.

I want to be like those saints who modeled for me that ongoing conversation, who, decades into the life of scripture, could ask me, a kid, a young adult, a younger believer: what do you think that verse means? How do you think I could live that out?

I want to follow the example of those aging witnesses who still, at seventy, eighty, ninety, were growing in mercy, kindness, patience. Like my grandmother, who at ninety, finally slowed by a series of small strokes, confessed, in a slow whisper: “I’m repenting my impatience. I was always so impatient with people who moved slowly. And now I move slowly. And I see how wrong I was.”

“Conversatio” suggests an ongoing willingness to re-examine, rethink, listen once again.

There are things I believe. Many.

I believe the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds. Wholeheartedly. I’ve gone over them repeatedly, with doubting teens, young adults from other backgrounds. I’ve spent time parsing the words, puzzling over alternatives. I’ve lined up other faiths, read reasons, tracked through questions, traveling back to the same place every time: I believe Jesus was who he said he was, son of God, Messiah, visible expression of grace and truth, firstborn of the new creation, conqueror of death.

I believe it. But I understand why many don’t. And even thought I’ve had more than my share of conversations with those of other faiths, of no faith, of uncertain faith, I want to continue the dialogue: because my own faith depends on it. Because my own compassion shrinks when I stop listening. Because I care what others believe, long to see truth together, understand, if only a little, what Jesus meant when he talked about heading out into the wild to find the wandering sheep. Even while I understand, more than a little, how offensive the image of wandering sheep can be to those who don’t share my belief.

I believe in a world imagined, intended, loved. That doesn’t mean I believe in a young earth, created in six twenty-four hour days. I’m troubled by those who insist they know how and when creation happened. The ancient language of the early Hebrews sings a song of loving intention, but the words leave wide latitude of interpretation. All our theories have holes large enough for dinosaurs to crawl through. I believe God used processes of expansion, of evolution, of artistic expression, processes we have yet to discover and have no name for, at the same time that he hovered, watched, prodded, laughed, sang, leaned in with delight as his great invention unfolded.

I understand the desire to nail things down. And I know my own ways of seeing seem narrow to some, and sometimes offensive (heretical?) to those committed to a binary way of seeing: this or that. Right or wrong. Evolution or design. I’ve been accused of side stepping issues, of “formica facts” (my friend’s rephrasing of my insistence on “counter-truths”). I lean toward paradox. Or what Wendell Berry calls “the way of ignorance.”

As I said, there are things I believe. I believe in a life after this one – although I don’t know what that will look like. And it’s not up to me to say who will be there.

I believe we are called to love. Although I am often clueless about what love would do in a given situation.

I believe I am often wrong. Often most wrong when I’m most certain I’m right.

Which is why I value conversation so highly. I’ve learned far more than I can tell from people whose experience of the world is very different from my own.

I think of my Jewish friends, Henry and Clifford, high school philosophers who patiently attempted to expand my horizons on everything from God to baseball.

I think of the reformed seminarians, confident young men whose theological certainties challenged my own and deepened my longing for grace, humility, and a deeper form of wisdom.

I think of my Irish Catholic friend, Ursula, whose experience of spiritual direction, mysticism, and mercy opened unexplored avenues of prayer.

I pause, reflect, give thanks for all those who have shared their stories over coffee, asked questions late into the night, prodded me, encouraged me, challenged me, shared books, ideas, insights, dreams.

I go back to Paul’s letter to the Romans: “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.”

What he’s describing is that conversatio morum Benedict spoke of: an ongoing conversion, a lifelong process of change that takes place as we wrestle, together, against the patterns of this world.

Ah – but that conversation is risky.

Think of Jesus – risking reputation to talk to the woman at the well, eating dinner in the homes of notorious sinners, encouraging, even affirming, the women who joined men in conversation.

Risky for him – but more so for the others: conversation with Jesus invited drastic change. The woman at the well, moving from isolation to bold witness. Zaccheus, the tax collector, upending his personal economy to disburse his dishonest accumulation of wealth. And Mary, sister of Martha and Lazarus. In what ways did conversation at Jesus’ feet lead her far from the safe, conventional roles of her day?

Where will real conversation lead us? Sooner or later – to conversion. Change of heart. Ongoing transformation. Benedict’s conversatio morum.

|

| Woman at the Well, Emmanuel Nsama, Zambia, 1970 |

Please join the conversation. What makes conversation difficult? How has conversation prompted change in your own life? What are the risks and rewards of conversation? What fears keep us silent?

Your thoughts and experiences in this are welcome. Look for the "__ comments" link below to leave your comments.

For a detailed, exegetical discussion of this topic, read Lois Malcolm's Conversion, Conversation, and Acts 15: "Conversion and conversation converge in the light of trinitarian theology and inthe book of Acts. The point of our moving beyond Jerusalem, of our outreach, is not to make others like ourselves, but to participate in an event that calls every-one involved out of themselves into something new and larger than themselves."