|

| John the Baptist Sees Jesus from Afar, J. J. Tissot, ca 1890, France |

The second week of Advent focuses on John the Baptist and

his message of preparation: “ Prepare the way of the Lord.” “Repent and be

baptized.”

I’ve been hearing about Jesus’s cousin John since I was

small, and have heard dozens of sermons focusing on his call to repentance. Yet

I’m still stumbling over parts of his story that surprise me, that remind me

how little I know of what it means to listen, prepare, repent.

Today’s Gospel reading is from Luke 3:1-6

In the fifteenth year of the reign of Emperor Tiberius, when

Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was ruler of Galilee, and his

brother Philip ruler of the region of Ituraea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias

ruler of Abilene, during the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas, the word of

God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness.

He went into all the region around

the Jordan, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins, as

it is written in the book of the words of the prophet Isaiah,

"The voice of one crying out

in the wilderness:

‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make

his paths straight.

Every valley shall be filled, and

every mountain and hill shall be made low, and the crooked shall be made

straight, and the rough ways made smooth;

and all flesh shall see the

salvation of God.'"

I’m struck, reading it this time, at the precision of Luke’s

historical context. John was clearly no mythical character, but a definite man,

in a very precise time and place.

More than that, though, he was a man of influence who walked

away from his place of privilege. The son of the priest Zechariah (some

traditions describe Zechariah as High Priest), he was raised to be a priest

himself.

Yet he appeared in the desert, far from his priestly

responsibilities and robes, dressed, according to Mark, in camel’s hair, with a

leather belt around his waist, subsisting on locusts and honey.

Reading those first verses again, I’m struck by an odd,

amusing thought: in the reign of all those powerful rulers (Caesar, Tiberias, Herod, Pilate,

Philip), in the time of those powerful high priests (Annas and

Caiphas) the word of God came to John in the wilderness.

To an unexpected person, in an unexpected place.

That word wilderness. Sometimes it’s translated desert. It’s

not a word we associate with Christmas preparation. We like evergreens,

candles, ribbons, snow.

Wilderness reminds me of Syria. Yemen. Somalia. Places we’d

rather not think of. People we’d prefer to ignore.

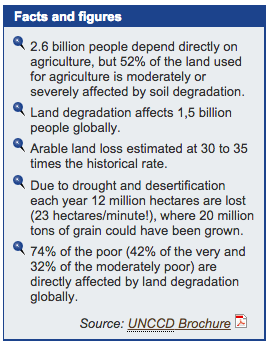

And desert. The UN predicts over 50 million people will be forced to leave their homes by 2020 because their land has turned to desert. Some of those people are pleading their cause in Paris this week at the Global Climate Summit. Many are already on the move, looking for food, for water.

We are halfway through the UN Decade for Deserts(2010-2020), and still many of our US leaders attempt to ignore the loss of

arable land, the fossil fuel impacts on fragile ecosystems, the unprecedented

displacement of entire populations.

We are halfway through the UN Decade for Deserts(2010-2020), and still many of our US leaders attempt to ignore the loss of

arable land, the fossil fuel impacts on fragile ecosystems, the unprecedented

displacement of entire populations.

John’s message was reversal: high places made low, low

places made high, crooked ways made straight, rough ways made smooth.

Dry places brought to life again? Flooded lowlands brought

back above sea level?

I wonder.

And his message was repentance: repentance for the

forgiveness of sins. Repent for the kingdom of Heaven is at hand. Repent and

believe the good news.

The prescribed Advent reading ends at verse six, but this

week I read on to the end of the chapter:

“Produce fruit in keeping with

repentance. And do not begin to say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our

father.’ For I tell you that out of these stones God can raise up children for

Abraham. The ax is already at the root of the trees, and every tree that does

not produce good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire.”

“What should we do then?” the crowd

asked.

John answered, “Anyone who has two

shirts should share with the one who has none, and anyone who has food should

do the same.”

Even tax collectors came to be

baptized. “Teacher,” they asked, “what should we do?”

“Don’t collect any more than you

are required to,” he told them.

Then some soldiers asked him, “And

what should we do?”

He replied, “Don’t extort money and

don’t accuse people falsely—be content with your pay.”

It’s puzzling that John leaps so quickly from “repent and be

baptized” to “produce fruit in keeping with righteousness.”

Puzzling that the fruit he describes has an economic edge to

it:

Share your extra shirts and food.

Don’t collect more taxes than required.

Don’t pad your own pockets at the expense of your neighbor.

Be content with your pay.

I don’t remember hearing that sermon.

Those who heard John and his message chose to go out to the

desert.

Turned from their preferred content providers in search of

the word of truth.

Listened long enough for their hearts to be moved, their

consciences stung, their wills rearranged.

Do we really want to listen?

A word of grief rises from the deserts of our world.

|

| © Hydropolitic Academy, 2014 |

For safety.

For water.

A longing for justice.

For land.

For food.

The voices are hard to hear, drowned out by the Christmas

ads, the candidate bluster, the smug repetition of acceptable lies.

Lord, I repent.

Repent of my hardness of heart, my failure to listen.

My collusion in a culture that ignores the cries of the

poor.

My complicity in an economic structure always reaching for

more.

My small gestures of generosity that fall far short of the

enormous divide between privilege and poverty, comfort and despair.

I repent, grieve, and ask, “What should we do?”

What would the fruit of righteousness look like, in this

time and place?

What would it mean to share my extra shirts and food with

people I will never see?

How will your reversal take place?

Merciful God,

how many John the Baptists,

how many prophets of your light,

have we ignored

because they were not what we were

looking for?

How many times have we ignored

voices

crying in the wilderness,

"Make straight the way of the

Lord."

How many times have we breathed a

sigh of relief,

and turned our backs on your

messengers,

because they did not speak the

message

we expected to hear?

Help us hear anew,

the cry of those who would lead us

to Christ.

Tune our ears to your heralds,

that we might also testify to your

light. Amen

(from The Abingdon Worship Annual 2008)

This is the second in a four week Advent series.

Earlier Advent posts on this blog:

Earlier Advent posts on this blog:

Advent One: Hope beyond Terror, Nov. 29,2015

Advent One: Hope is Our Work, Nov. 30, 2014

Advent Two: Peace is Our Promise, Prayer and Practice, Dec. 7, 2014

Advent Three: Love is the Air We Breathe, Dec. 14, 2014

Advent Four: Joy is the Song We're Given, Dec. 21, 2014

Advent One: Rethinking Portfolios, Dec. 1, 2013

Advent Two: Resisting Idols and Injustice, Dec. 8, 2013

Advent Four: Rejoicing in Mystery, Dec. 22, 2013

Advent One: How Do I Know? Dec. 2, 2012

Advent Two: Outsiders In Dec. 9, 2012

Advent Three: Question. Fruit. Dec. 16, 2012

Advent Four: Sing Alleluia, Dec. 23, 2012

Advent One: What I'm Waiting for, Nov. 26, 2011

Metanoia, Dec 4, 2011

Voice in the Wilderness, Dec. 11, 2011

Advent Two: John the Baptist, Dec. 12, 2010

Mary's Song, Dec. 19, 2010

Christmas Hope, Dec. 24, 2010

+Jarjan+Jordan+2012.jpg)