Our church has been studying the last half of Genesis. My morning reading with Encounter with God this week landed in the same chapters. The title for yesterday morning's notes was ominously titled The Temptations of Empire:

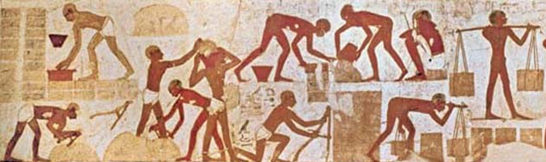

As the famine continues and extends its reach across the whole region, Joseph achieves the pinnacle of his power in Egypt. He devised a system which kept mass starvation at bay, and the writer records that “he brought them through that year with food”. However, this success came at the price of the liberty of the people who were “reduced… to servitude”. The devising of an economic system which kept the population alive was a great achievement, but it resulted in a dangerous centralizing of power which, as the story of Exodus will reveal, led to oppression and slavery.

Walter Brueggamann makes this point in a sermon called "The Fourth-Generation Sell-out." He asks why, given four sets of ancestral

stories in Genesis (Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph), God is spoken of repeatedly in

reference to only three: “the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob."

Walter Brueggamann makes this point in a sermon called "The Fourth-Generation Sell-out." He asks why, given four sets of ancestral

stories in Genesis (Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph), God is spoken of repeatedly in

reference to only three: “the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob."

Why

wouldn't Joseph, most powerful of the four, be included?

According

to Brueggemann, Joseph’s name was dropped because he conducted the imperial

work of Pharaoh. Given opportunity to be a blessing to the nations he became

instead an agent of empire:

Joseph proceeds to do more than interpret. He advises. He is a "consultant." . . . Joseph achieves for Pharaoh, by his rapacious, ruthless wisdom, a monopoly of food that becomes for Pharaoh an economic tool and a political weapon." Joseph victimized the Egyptians and eventually his own people as well.According to Brueggemann, "he becomes the manager and chaplain of the nightmare of empire."

We are in a nightmare of empire of our own.

Our democracy, our country, our state, our political

parties are all in upheaval: all held captive by powerful men who have

compromised with evil and used privilege to harm those they promised to

protect.

I believe many of our leaders start out, like Joseph, determined to serve

well, then fall prey to temptation.

Surrounded by privilege and power, it's so tragically

easy for them to lose their way.

I met one state representative who never stays in

Harrisburg because, he says, "It's too easy to be sucked in. To think it's

normal to be wined and dined by lobbyists. To think it's okay to use power to

maintain my own position."

I've spoken with legislators who were genuinely thankful

when they lost a race for re-election: "I'm not sure I realized how

dysfunctional it was until I was forced to step away."

They had no say in the way the drama played out.

Struggling to survive,

they acquiesced to Pharaoh’s power and Joseph's ruthless greed.

We do have a choice.

And the moral responsibility to watch, pray, learn,

speak, vote.

Our choices impact not just us but those who have far

less choice: children in impoverished communities, men and women incarcerated without

fair trial or reasonable bail, refugees fleeing oppressive regimes, people in

nations across the globe who watch with alarm as our country careens toward war

with Korea or capriciously withdraws from carefully drafted attempts to manage pressing concerns.

On a global scale, our voices are loud.

Our choices matter.

Even off-year elections matter.

They determine what kinds of policies

will move forward, what tone will govern party platforms, what kinds of leaders

will be encouraged on their way.

And

conversations matter.

What we repeat. Who we applaud. What we hope for. How we

pray.

I pray for leaders who demonstrate humility, wisdom,

courage.

I pray for Christians able to hear, discern and speak the

truth.

I pray we remember the command to love our neighbor and the promise that perfect love casts out fear.

I pray for a platform of justice and mercy, a church that remembers God's heart for the poor, the defenseless, the stranger, the worker.

We bid you, stir up those who can change

things;

do your stirring in the jaded halls of government;

do your stirring in the cynical offices of the corporations;

do your stirring amid the voting public too anxious to care;

do your stirring in the church that thinks too much about purity and not enough about wages.

do your stirring in the jaded halls of government;

do your stirring in the cynical offices of the corporations;

do your stirring amid the voting public too anxious to care;

do your stirring in the church that thinks too much about purity and not enough about wages.

Move, as you moved in ancient Egyptian days.

Move the waters and the flocks and the herds

toward new statutes and regulations,

new equity and good health care,

new dignity that cannot be given on the cheap.

Move the waters and the flocks and the herds

toward new statutes and regulations,

new equity and good health care,

new dignity that cannot be given on the cheap.

Some earlier posts about political issues can be found here: What's Your Platform